by Robert van Kan

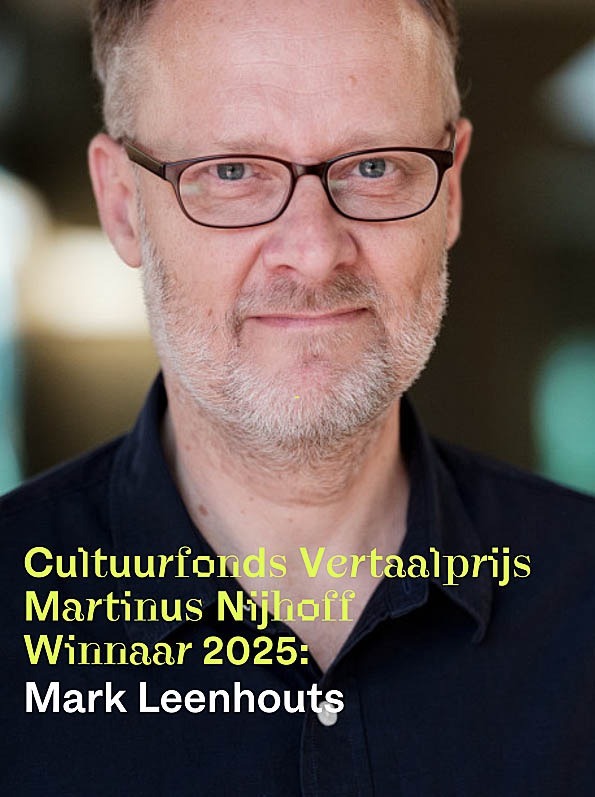

On 12 September, sinologist Mark Leenhouts was awarded the Martinus Nijhoff Prize 2025, the prestigious literary translation prize of the Cultuurfonds, for his translations from Chinese. The jury describes him as an advocate of both the Chinese and Dutch languages: his work opens worlds, connects perspectives and enriches the literary landscape.

On the occasion of this recognition of Leenhouts’ oeuvre, Robert van Kan – friend and fellow Sinologist – speaks with him about his career as a translator of Chinese literature, about highs and lows, and about the ins and outs of the craft.

Mark, first of all, congratulations on winning the Martinus Nijhoff Translation Prize. It is a wonderful recognition of a long career as a translator of Chinese literature. How did your journey as a translator begin?

I always loved language and literature, that’s also the reason I wanted to study Chinese, I wanted to know everything about those weird characters! So it had been in the cards for a long time that I would be involved in something like this, but things still had to fall into place. In Leiden, we had our teacher Wilt Idema, himself a translator, who showed me that being a translator is something you can be or become. There was also a younger generation of translators emerging under him; many sinologists were already working on a book. But the realization came in Paris. After studying Chinese in Leiden for three years, I went to Paris in 1990, to the Université Paris 7. There I had a teacher of Chinese literature, Madame Tan. For her, literature was not just words on paper – she breathed life into them. In Paris, I also noticed how much more Chinese literature had already been translated there. I loved browsing the bookstores, and most of them had an entire shelf full of translated Asian literature. It was in vogue, people bought it, talked about it.

How did that interest in translation lead to your first book?

At one point, Madam Tan held up a book that had just been published in French, by a certain Han Shaogong. “This is an interesting book,” she said, “just translated, about a man living in the Chinese mountains who cannot speak.” She didn’t say more about it. I read it and it was a remarkable story, it immediately intrigued me. Also because I saw this it in the bookstores and people bought it. Maybe I should translate that book into Dutch, I thought.

From Paris I went to China to study there for a year. In China you helped me further, we then traveled together across the country, from Beijing to Hainan. We went to South Hunan, the place where the story takes place. The district was not yet open to foreigners and we hadn’t applied for permission. Since it was Chinese New Year, the police didn’t want any hassle, so we were allowed to stay if we disappeared on their next working day. They even put us in the luxurious local police guesthouse! We knew that Han Shaogong lived on Hainan. Because you worked at the embassy, you had traced the address of the local writers’ union. Instead of making an appointment, as one should, we simply rang the bell. He wasn’t home, but that evening he came to our hotel. That’s how I met him. That evening I asked if I could become his translator. He said yes, and I am still in contact with him to this day. I even wrote my dissertation about him and translated two more of his books. So the first ten years of my career revolved largely around him. Back in Leiden, my teachers helped me with contacts with publishers. That’s how I ended up with Eric Visser of De Geus publishers. He was amused by this young guy, freshly graduated, arriving with great ambitions. I had a bag full of books I wanted to translate – clearly I had no idea how that worked. But he said: “Let’s do it!” That’s how ‘Ba ba ba’ by Han Shaogong became my first book.

You have now translated 14 or 15 books, including The Dream of the Red Room, a 2000-page work in four volumes, together with Anne Sytske Keijser and Silvia Marijnissen. What are the highs and lows of the life of a literary translator?

The highlight is unquestionably that every day you get to work on a book you love and in which you can lose yourself in. I completely immerse myself in it. At my little desk, surrounded by books. Preferably a book that challenges me. If it isn’t difficult, it isn’t fun. Being able to spend the entire day with a book you think is beautiful. That is and remains the greatest joy.

The downside is that Chinese literature is not widely known, nor widely read or sold. It can sometimes be hard to get a beautiful book translated. Publishers are cautious. It is a challenge to find work that is beautiful and has potential to be published.Many of my colleagues who translate from French have a broader palette to choose from: old, new, experimental, every genre. There is a wider readership for French literature. So sometimes it is difficult to work in a niche. On the other hand, in almost all cases I have proposed the works myself; I rarely translate what others ask me to.

The jury report states that you possess not only a phenomenal knowledge of Chinese but also of Dutch. In the examples given, you sometimes translate quite freely, because Chinese is often imposs to render one-to-one. You then inject your own personality or creativity into someone else’s work. How do you approach that?

Yes, that freedom is true. Yet I remain faithful to the original, perhaps not to the letter, but certainly to the spirit of the text. As a translator from Chinese, you have to tinker a lot with sentences – even seemingly simple ones – much more so than when translating from German or French. With Chinese, you must do more to do justice to the text. If you were to translate it literally, it produces ugly Dutch or loses meaning. Chinese, for example, has many four characters expressions that can alost never be translate literally. You have to work with them. You consider the idea behind the expression, its history, the story, the sound, the rhyme. You never translate word-for-word, you search for the right meaning of a word in that sentence, in that paragraph, on that page, for that writer, in that style.

Chinese is therefore a context language, requiring deep knowledge of the work’s broader context. You have translated both classical and modern literature. You have looked so deeply into the soul of Chinese culture. What is the most important insight you have gained from that?

If there is a red thread running through all those books, it is a strong engagement with the world around you. In the Western novel, you are often in the protagonist’s head from page one. European and American writers are valued for digging into an individual, examining their deepest soul. The main character must undergo development, discover something about themselves, process a childhood trauma, for example. That also shapes the structure of the book, it drives a strong plot. In Chinese literature, that is far less common. Readers tell me that too. Many characters don’t fully reveal themselves and seem to remain seemingly flatter. The storyline is less defined, it builds less towards a tight plot. That is partly traditional, and still true today. It is not that the ‘I’ plays no role, but it expresses a deeper sense that the individual is not the center of the world or of nature. Humans stand in a world with other people, and must relate to that world. The gaze is more outward, toward what is happening around us.

Do you mean that we live in an individualized society, where the self is central, while the Chinese live more in a society in which the collective plays a greater role?

Yes, the characters gain depth through interaction with others. There are often multiple protagonists, often in paires, positioned in various relationships to one another. They reveal themselves through contrast with others. Most Chinese writers and classical poets didn’t consider it particularly artistic to dig into the deepest inner or intimate feelings of a character. They simply didn’t find that very relevant.

Do you see traditional values reflected in those relationships – teacher and student, father and son? And is literature meant to affirm those values, or to challenge them?

That is indeed the Confucian side of art; What is a person’s role in society? But there is also a deeper, Taoist side to literature: the relationship between human and nature. This also applies to art in general, not just literature. Just look at Chinese landscape painting. You see massive mountains, drifting clouds, and a tiny human, usually somewhere at the edge. It shows that man is only part of nature, and often only a very small and insignificant part. For Western readers, that perspective can be a challenge. Chinese characters do not easily bare their souls, and we also project that onto how we see China; a country that does not reveal itself. But when I’m in China, I recognize how people look at the world and at one another. It is less ‘me-centred’. Reality and literature align well in that sense.

You have now also translated what is perhaps the most famous Chinese work, The Art of War, by Sunzi. It is the first time this work has been translated directly from Chinese, even though several Dutch versions already exist. How is that possible?

I think there has been a reappraisal of the original text of this work. For a long time it was seen primarily a manual on warfare. In the broader history of Chinese literature, it did not hold a prominent place. Since the eighties, we mostly knew it through adaptations for the business world. It became a kind of self-help book for managers and psychologists. In reaction, we have seen a rediscovery with Sinology since about 2000, recognizing it again as a philosophical and literary text, also in relation to the other classical works. That’s why it has never been translated directly from Chinese before, and we always worked with translations from English. Indirect translation inevitably dilute the text. A translator working from English is usually unfamiliar with the Chinese cultural or literary context. Publisher Athenaeum, which also published the ‘De Droom van de Rode Kamer’ is known for its classic editions that go back to the source text. They asked me to stay close to the original, and not impose a strictly military or other interpretation. I loved workin on it, it taught me a so much. It was also extremely difficult. It truly was a real journey of discovery, for instance, uncovering its message that warfare should be avoided whenever possible, through strategic thinking.

https://www.singeluitgeverijen.nl/athenaeum/boek/de-kunst-van-het-oorlogvoeren/

https://www.singeluitgeverijen.nl/athenaeum/boek/de-droom-van-de-rode-kamer/

In conclusion, we have seen that you are not only exceptionally strong in Chinese, but also at in Dutch, you aim for beautiful, and you are both creative and inventive. So when can we actually expect your first novel?

I can’t deny the thought has never crossed my mind. But I also don’t believe that every translator is a frustrated novelist. The big difference is that as a translator you begin with a text, whereas as a novelist you start with a blank page. That is an entirely different order of things. I’m not sure I can do that. Who knows!

Robert van Kan is director of the education consultancy Edvance Education International, based in The Hague and Beijing.

Also read the Jury report : https://cms.cultuurfonds.nl/assets/downloads/Juryrapport-Vertaalprijs-2025.pdf

and the laudation delivered by Fresco Sam-Sin during the award ceremony: